Study design and ethical considerations

This cohort study – the Brazilian Ribeirão Preto and São Luís Birth Cohorts (BRISA, acronym in Portuguese) – was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee (Approval Number 4771/2008-30) on April 8, 2009, and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. All participants signed an informed consent form. Participants’ anonymity and data confidentiality were guaranteed, as were the principles of beneficence and non-maleficence. This study was reported following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

Study location

São Luís is the capital of the state of Maranhão, located in the Brazilian Northeast region. In 2010, the city had 1,014,837 inhabitants and 21,930 hospital births. Infant mortality reached 17.36 per 1,000 live births. The municipal Human Development Index was 0.768, with the city occupying position 1,472 among the 5,570 Brazilian municipalities35. The fluoride levels in the public water supply in São Luís ranged from 0.60 to 0.84 ppm across the different districts36.

Sample size

This sample of 865 mother-infant dyads had a power of 84.02% to identify statistically significant correlations between SUDP and dental caries, considering an alpha value of 5%, a correlation coefficient of 0.025 (study data), and a delta value of 0.1 in two-sided tests.

Sampling procedure

The data were collected during three different periods between January 2010 and March 2013: during antenatal care (baseline or T1), first follow-up at birth (T2), and second follow-up at age 12–36 months (T3). A total of 1,447 pregnant women were recruited between February 2010 and June 2011 (T1). Of these, 66 did not attend the follow-up visits or did not answer the questionnaires. Between May 2010 and November 2011, 1,381 (93.94%) women were followed up at the time of the baby’s birth (T2). Subsequently, 1,160 children (80.2%) were re-evaluated between September 2011 and March 2013 but only 865 underwent the dental examinations (T3).

The study sample was selected by convenience sampling, considering that a representative random sample of pregnant women could not be obtained since there are no reliable records of pregnant women or women receiving antenatal care in the state of Maranhão. Thus, the pregnant women were selected during visits to public and private health centers for their antenatal/follow-up care and were referred to the University Hospital of the Federal University of Maranhão (HUUFMA) to undergo ultrasound examination. The criteria for inclusion in the study were undergoing an ultrasound scan before 20 weeks of gestation and baseline assessment between 22 and 25 weeks of gestation. If the women met the inclusion criteria, they were asked to answer the questionnaires and were submitted to other assessments. After birth, the women’s babies were also included in the study.

Data collection

Face-to-face interviews and self-administered questionnaires were applied to the children’s mothers at baseline and during the 1st and 2nd follow-up consultations. Data were also obtained from the medical records and children’s dental examinations.

Independent variable

SUDP was a latent variable consisting of licit (alcohol and tobacco) and illicit (merla, cocaine mix, marijuana, cocaine, crack, among others) drug consumption. The respondent was asked whether she had used any drugs (marijuana, merla, cocaine, crack, or others) during the three months before or during the current pregnancy. Licit drug consumption was determined based on four questions: “Did you smoke during the current pregnancy?”; “During pregnancy, did you drink wine?”; “During pregnancy, did you drink beer?”; “During pregnancy, did you drink any other type of alcoholic beverage like whiskey, vodka, gin, rum, cachaça, caipirinha, or beat?”.

Covariates

At baseline (T1), the following data were obtained by face-to-face interviews: maternal age (< 24, 25 to 34, ≥ 35 years); SES (A, B, C, D, and E) according to the Brazilian Association of Population Studies (ABEP, acronym in Portuguese)37; household income (in minimum wage for the baseline year 2010); mother’s educational level (in years of schooling), and conditional cash transfer program (dichotomous variable). Data on the symptoms of MPD, such as stress, anxiety, and depression, were also collected using self-administered questionnaires. Stress symptoms were assessed using the perceived stress scale (PSS-14). This tool consists of questions about feelings and thoughts in the previous month. A score is assigned to each answer. The scores are then summed to indicate the level of stress: low level of stress (0–13), moderate level of stress14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26, and high level of stress27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,38. Anxiety was assessed using the Beck Anxiety Scale39 and classified as low level of anxiety (0–21), moderate level of anxiety22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35, and potentially troubling anxiety (≥ 36). Depression symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Depressive symptoms during pregnancy were categorized as no possibility of depression (CES-D < 16) and with depressive symptoms (CES-D ≥ 16)40.

In the 2nd follow-up (T3), data were obtained by face-to-face application of questionnaires to mothers regarding exclusive breastfeeding for six months, night bottle use, breastfeeding duration, sugar consumption, and child’s age (in months). Sugar consumption was evaluated based on foods and drinks consumed on the day prior to the interview using a 24-hour dietary recall. The latter is a valid assessment tool for analyzing habitual nutrient intake on the previous day, as demonstrated in a study using the same population sample41. The mother/guardian reported the foods and drinks the child had consumed. The frequency of added sugar consumption was categorized as follows: up to 1 time/day and > 1 time/day42. Given the lack of children without sugar consumption in the sample, this cutoff point was adopted to maintain power in both categories, preserving the possibility of comparing lower and higher sugar consumption.

The diagnosis of DDE was made according to a modified version of the index proposed by the World Dental Federation43. DDE were characterized by teeth with enamel hypoplasia, diffuse opacities, or demarcated opacities, scored from 0 to 8: 0 – normal; 1 – demarcated opacity; 2 – diffuse opacity; 3 – hypoplasia; 4 – other defects; 5 – demarcated and diffuse opacity; 6 – demarcated opacity and hypoplasia; 7 – diffuse opacity and hypoplasia, and 8 – all three defects. DDE were included in the analyses as a dichotomous variable.

The dentist evaluated GBoB at the end of the clinical examination (used as a proxy measure of oral hygiene)44,45,46. After brushing, GBoB was assessed on the buccal, palatal/lingual, mesial, and distal surfaces as follows: 0 – absence; 1 – presence; 2 – exfoliation/unerupted tooth. Unevaluable and unerupted teeth were not included in this analysis. GBoB was included in the analyses as a dichotomous variable. Brushing with fluoridated toothpaste was obtained with a questionnaire answered by parents/guardians.

Dependent variable

The incidence of dental caries in children was the dependent variable. Dental caries was identified based on the number of teeth with active or inactive caries lesions, which were classified using the Nyvad criteria47: 1 – active caries without surface discontinuity (intact surface); 2 – active caries (microcavity); 3 – active caries (cavity); 4 – inactive caries (intact surface); 5 – inactive caries (microcavity), and 6 – inactive caries (cavity).

The dental examinations were performed at the Maternal and Infant Health Unit (HUUMI) of HUUFMA following World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations: under artificial lighting using a periodontal probe, a mouth mirror (©2013 Hu-Friedy), compressed air, distilled water, and a three-way syringe. All materials were previously sterilized and individually packaged. Six trained examiners conducted the procedure for the diagnosis of dental caries. The intraexaminer kappa value for detecting caries in a child was 0.86.

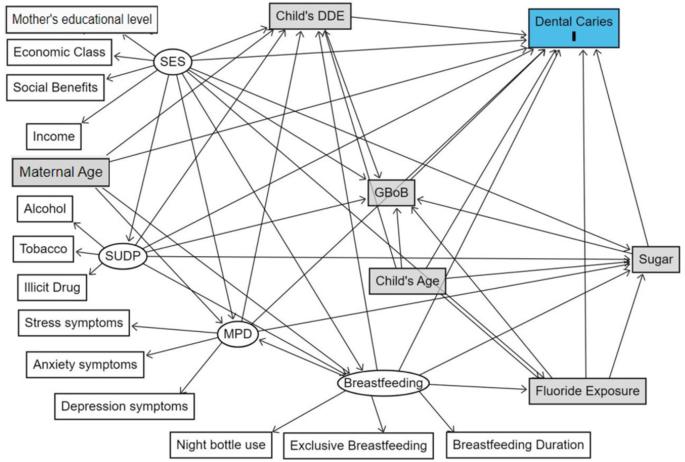

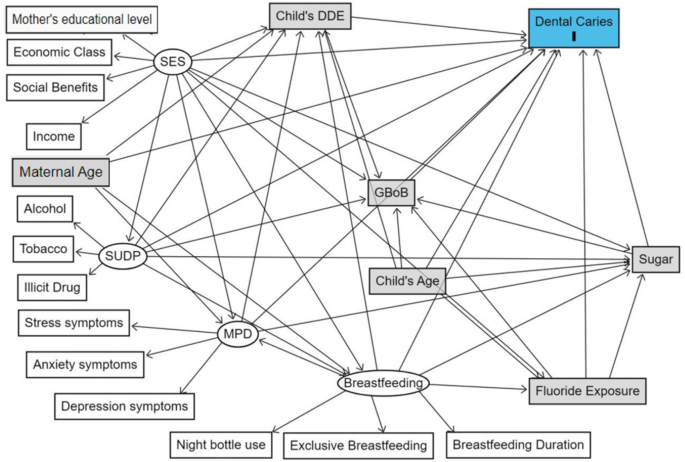

Theoretical model (Fig. 1)

Theoretical model of the association between substance use during pregnancy and childhood dental caries. SES socioeconomic status, MPD minor psychiatric disorders during pregnancy, SUDP substance use during pregnancy, DDE developmental defects of enamel.

The primary outcome of the study was the number of decayed teeth in children aged 12–36 months. SUDP was the primary exposure, considered a latent variable, which was inferred from the following observed variables: alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use. Three other latent variables were also included: SES, MPD, and feeding history. The SES was obtained from the shared variance of three observed variables: economic class, mother’s educational level, and occupation of household head. MDP was a latent variable obtained as the covariance of symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression. Breastfeeding consisted of three observable variables: exclusive breastfeeding for six months, use of a bottle at night, and duration of breastfeeding. Thus, our study raised two hypotheses regarding the possible effects of SUDP on dental caries: (1) Tooth Development Hypothesis, and (2) Behavioral Hypothesis.

According to the first hypothesis, women of low SES are more vulnerable and are therefore more likely to experience symptoms of MPD48 and SUDP. Substance use, in turn, could interfere with the development of the fetus during pregnancy, consequently causing DDE. The consumption of alcohol and drugs can contribute to hypocalcemia, hypoxia, and pyrexia, as well as to decreased nutrient absorption, thereby compromising tooth development at three stages: ameloblast secretion, mineralization, and maturing12. These factors would facilitate future biofilm adhesion to the children’s deciduous teeth, thus causing dental caries10,11,13, as reported in a previous study suggesting that children exposed to chemical substances in their mother’s uterus are at a greater risk of developing caries during childhood24. Additionally, systematic reviews indicate that DDE is a potential risk factor for tooth sensitivity, enamel fracture, and dental biofilm accumulation, thus accelerating the progression of dental caries12. This relationship could also be explained or mediated by other variables. One of these indirect paths involves impaired access to oral hygiene, causing gingival inflammation and caries49. Otherwise, there is evidence that such an association between DDE and dental caries does not exist50.

The other hypothesis that links SUDP to caries would involve low SES, MPD, and inappropriate care behaviors concerning food intake and hygiene of the child. The lower the SES and the higher the prevalence of MPD and SUDP, the worse the access to a healthy diet51. Drug users often have a low-nutrient diet, consuming especially refined carbohydrates, and are reckless with their oral hygiene and that of their children52,53. Maternal age can be an indirect path that links drug use, diet, gingival bleeding, and dental caries, as younger women are more likely to have some contact with drugs54. Furthermore, adolescents and young people tend to pay less attention to diet and the difficulty in oral hygiene care such as brushing with fluoridated toothpaste52. The increase in the child’s age contributes to the increased frequency of foods rich in added sugars. This diet is usually more cariogenic and these mothers breastfeed less and use more night bottles containing sugar to feed their children, resulting in more dental caries.

Data analysis and processing

The present study performed descriptive analyses, estimating absolute frequencies, percentages, means (± standard deviations), and respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare the frequencies of the variables between the groups of women who used or did not use the following substances: (i) alcohol, (ii) tobacco, and (iii) illicit drugs.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was applied to test the hypotheses of the study. This technique is used to simultaneously address multiple dependency relationships and can identify concepts not observed in these relationships, reducing the measurement error during the estimation process. This statistical method estimates a series of multiple regression equations and enables the simultaneous testing of associations through direct and indirect paths (mediated by the action of other variables), as well as the establishment of latent variables (theoretical constructs)55.

Our study estimated the factor loadings (FL) of each latent variable and the standardized coefficients (SC) and P-values for each model. We adopted robust weighted least squares means and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimation since the models are composed of continuous and categorical variables. Theta parameterization was employed to control for differences in residual variance. The following model fit indices were calculated55: (a) chi-square test (χ2) with a p-value greater than 0.05; (b) Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) less than 0.05, with an upper 90% CI limit less than 0.08; (c) Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) greater than 0.9555. The total, indirect, and direct effects of the exposure on dental caries were also estimated using bias-corrected bootstrap estimates, powerful mediation tests, and robust to small deviations from normality56. The STATA 16.0 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, USA) and Mplus, 7.31 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, USA) were used for the analyses, considering an alpha value of 5% as a criterion for rejecting the null hypotheses.

link